Nowadays, we all know about photosynthesis – the process that plants (and some bacteria) use to produce their own food. Photosynthesis not only provides food for plants but also is responsible for feeding nearly all life on Earth. It is also thanks to photosynthesis that our planet has conditions allowing life to develop, such as an atmosphere with oxygen.

We also know that photosynthesis is the process by which plants use sunlight to convert carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O) into carbohydrates (or sugars) and release oxygen (O2).

However, humans did not always know how plants got their food. People have been interested in how plants get the nutrients they use to grow for a very long time. The early Greek philosophers believed that plants got all their nutrients from the soil. This was a common belief for many centuries. It was only in the first half of the seventeenth century that scientists decided to investigate to be sure.

The process of photosynthesis is so important and so complex that some of its phases are still not completely understood. Many scientists have helped us understand what we know so far, and many others are still making discoveries in the field. Here, we are going to see thirteen of the experiments that helped us unravel the secrets of how plants grow.

1. Are plants getting their food from the soil? – Jan Baptiste van Helmont’s experiment

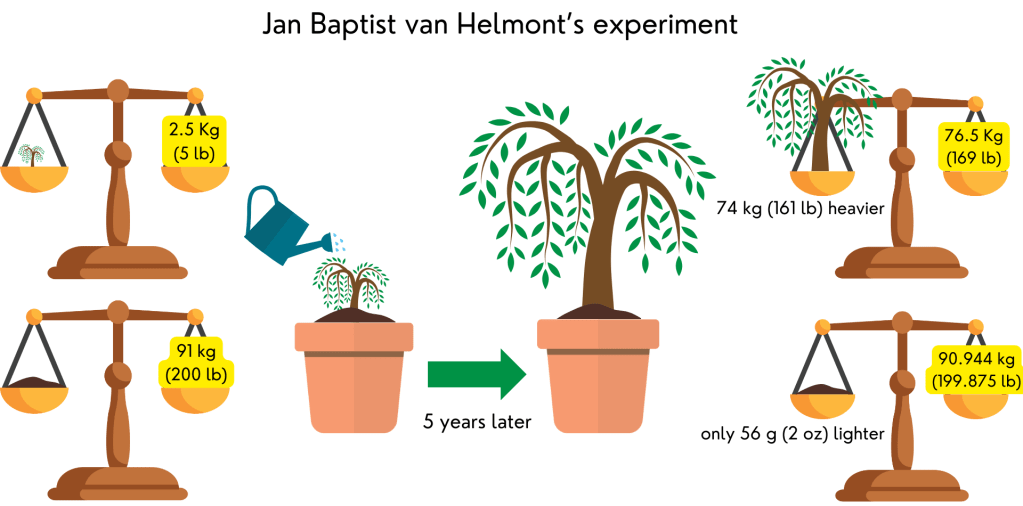

Jan Baptiste van Helmont, a Dutch physician (or medical doctor) and scientist, was the first to conduct an experiment to understand where plants get their food. He planted a willow tree weighing 2.5 kg (5 lb) in a clay pot with 91 kg (200 lb) of soil. He watered this tree as needed and cultivated it for 5 years. After 5 years, he removed the tree from the pot and weighed it. The tree had grown and now weighed 76.5 kg (169 lb). He also weighed the pot to see how much soil it had lost. The result was only 56 g (2 oz).

Because the tree grew using just a tiny amount of soil, he concluded that the tree grew not by “eating” soil, but by “drinking” water. At the time, he did not understand the role of sunlight and atmospheric gases (CO2) in plant growth. Even though it may seem very basic today, his experiment was the first to prove the Greeks were wrong, and that plants need water to grow.

2. Is it just water or is there something else? – John Woodward’s experiment

In 1699, still in the seventeenth century, an English scientist named John Woodward performed experiments growing plants with no soil and only water (this type of cultivation is called hydroponics), trying to test van Helmont’s idea and to quantify how much water was needed for plants to grow. He grew plants using water of different purity, such as rainwater, river water, drainage water, and others. He found that most of the water that the plant absorbed was expelled through the pores and released into the atmosphere. He concluded that plants need more than water to grow.

So, plants could grow in the soil or only in water, but they didn’t take what they needed to grow from the soil or the water. How do they grow then? It was still a mystery, and it took almost a hundred more years for scientists to start to understand a little better how plants grow.

3. Plants interact with the atmosphere are important to life – Joseph Priestley’s experiments

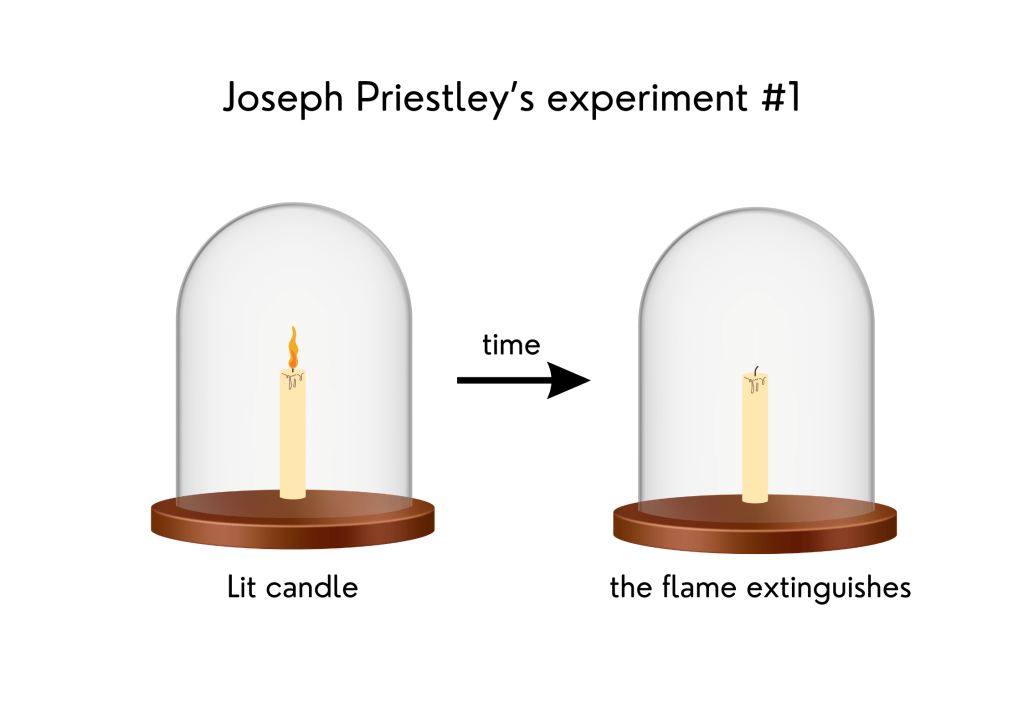

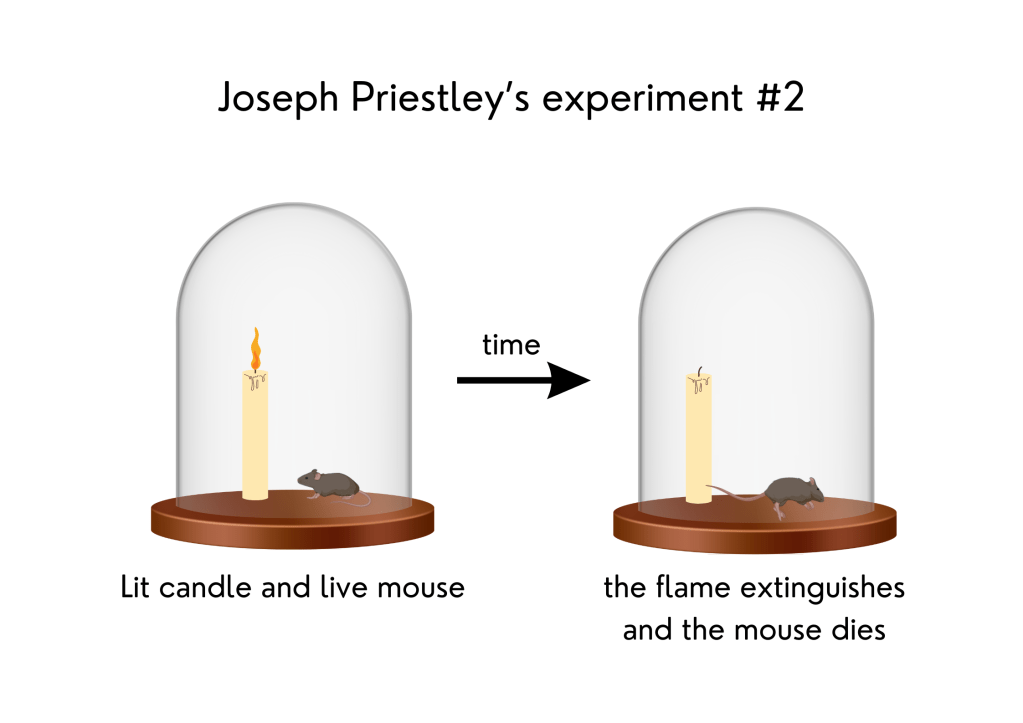

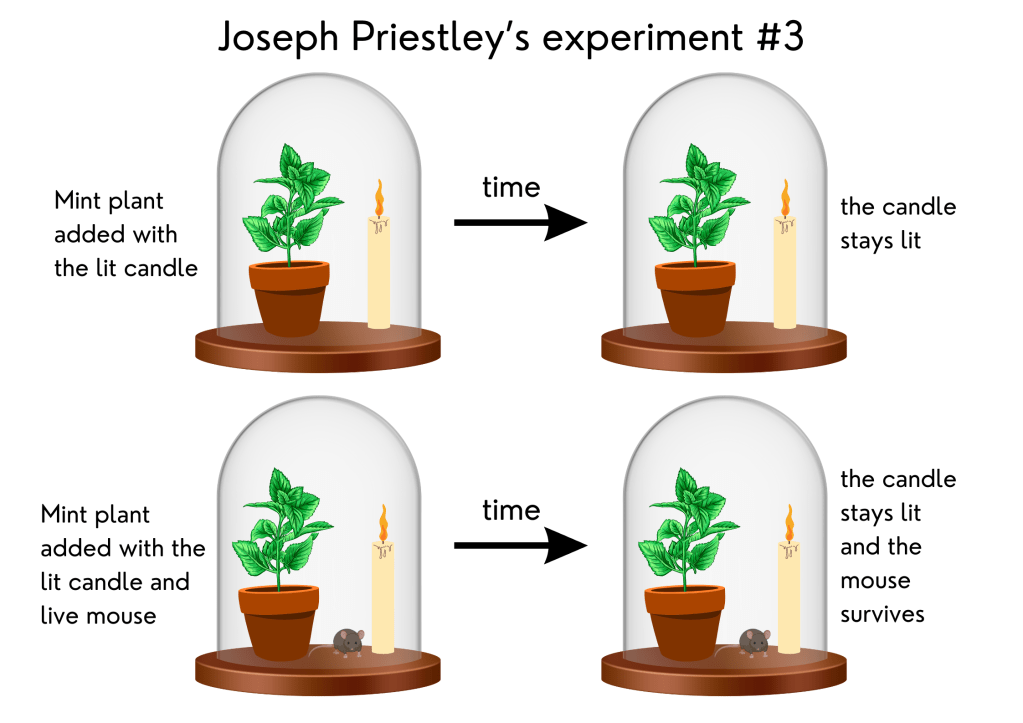

In 1771, English scientist Joseph Priestley performed a series of experiments demonstrating the importance of atmospheric gases to plant growth. People in Priestley’s time believed that a toxic substance, which they called “phlogiston,” was produced when a flame was burned. If a mouse were put under a dome with a burning candle, this substance would kill the mouse. Priestley conducted three different experiments with candles.

In the first one, he placed a burning candle under a dome and observed that soon the flame was extinguished. In the second, he put a mouse under the dome where the candle had burned and found that the mouse did not survive. In the third experiment, he placed a mint plant under the same dome as a burning candle, and in another dome, he put a mint plant, a burning candle, and a mouse. The mint plants in both domes kept the candles burning and the mouse alive. He concluded that the mint renewed the air inside the domes, chemically removing the “phlogiston.” At that time, he did not know that plants produce oxygen, necessary to both make the candle burn and keep the mouse alive. He thought that only the plant growth was responsible for that and did not account for the need for sunlight.

Representation of Joseph Priestley’s experiments with candles in 1771

4. It needs sunlight! – Jan Ingenhousz’s experiment

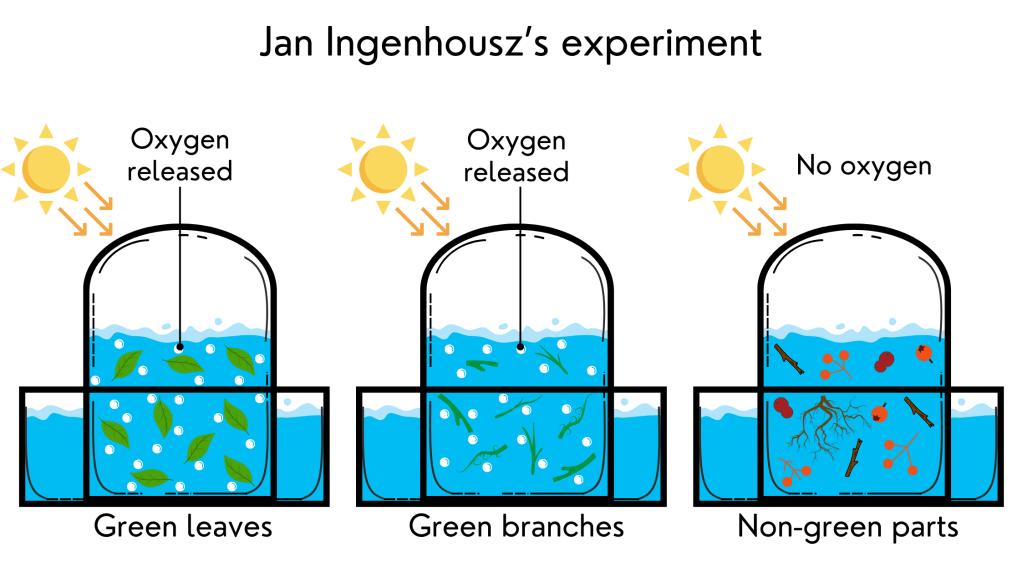

Jan Ingenhousz, another Dutch physician, was the one who showed the importance of sunlight for plants to be able to grow and produce oxygen. In 1778, only seven years after Priestley’s experiments, he performed a similar experiment. He took different plant parts (leaves, green branches, brown branches, roots, and fruits), placed them in flasks with water, covered these flasks with transparent domes, and exposed them to sunlight. He noticed that, in the presence of light, plants produced some type of gas as bubbles in the water. But not all plant parts: only the green ones. He concluded that sunlight is important for plant growth, but the green pigment of plants is also very important.

Another very important experiment that had nothing to do with plants, but helped us understand plants better – Antoine Lavoisier’s experiment

As Ingenhousz was preparing his experiments, the famous French chemist Antoine Lavoisier demonstrated that “phlogiston” did not exist. That means there was no substance that flames produced and released into the air that could kill animals. What happened in Priestley’s experiments was that flames need oxygen to exist, and animals need oxygen to survive. The dome placed over the candle and the mouse limited the amount of oxygen available, and when it ended, the flame extinguished and the mouse died. Lavoisier’s experiment made it clear that the plants in Priestley’s and Ingenhousz’s experiments produced oxygen when illuminated by sunlight.

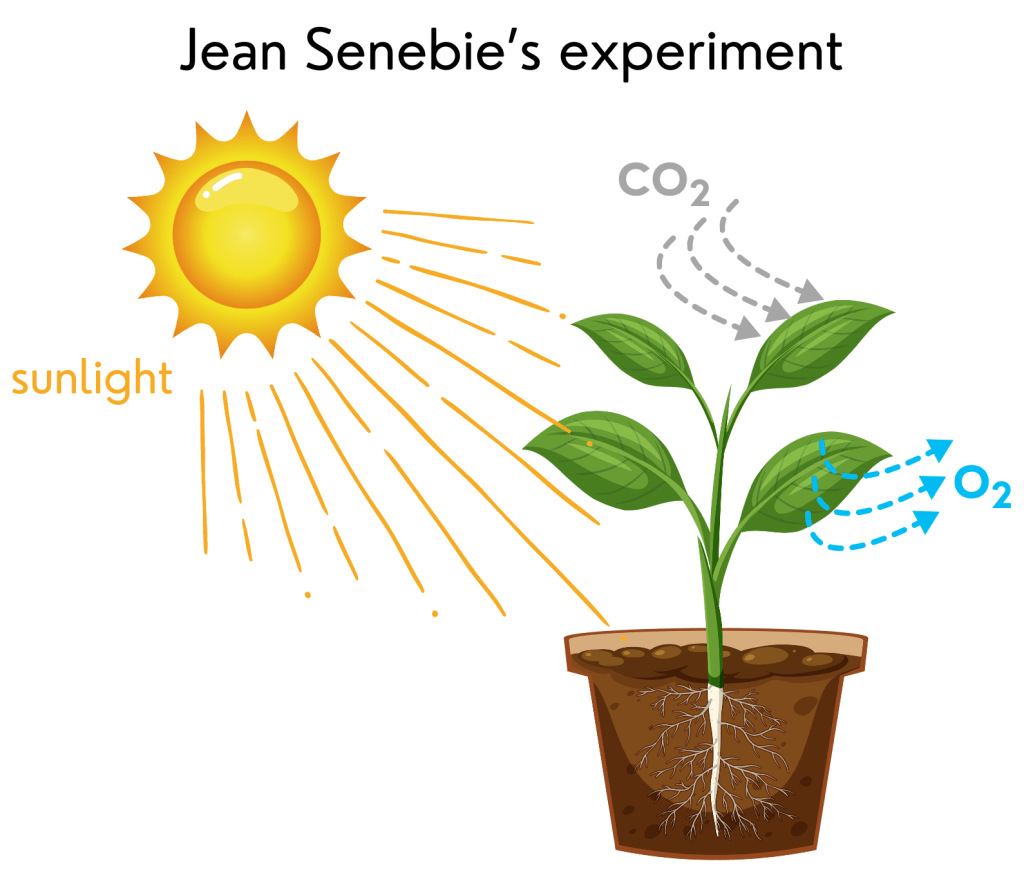

5. Plants consume carbon dioxide and release oxygen – Jean Senebier’s experiment

In 1796, Jean Senebier, a Swiss pastor, botanist (a scientist who studies plants), and naturalist (a scientist who studies nature), showed that plants consume carbon dioxide (CO2) from the air and release oxygen under sunlight. Lavoisier’s and Senebier’s experiments made Ingenhousz rethink his results. He concluded that plants use sunlight to split CO2 and use its carbon (C) to grow and release oxygen (O2) as waste.

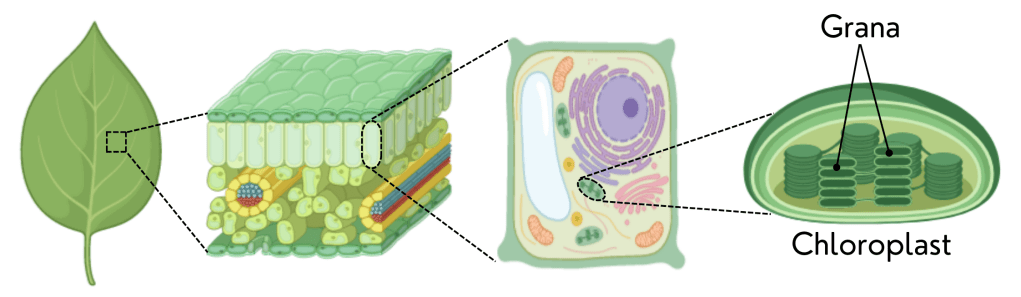

6. Chlorophyll and chloroplasts – the contribution of four different scientists

In 1816, Joseph Pelletier and Joseph Caventou, two French chemists and pharmacists, were able to isolate a molecule from leaves that was responsible for their green colour. They named this molecule chlorophyll, as a reference to the green colour (in Greek: chloro) of the leaves (in Greek: phylum). Twenty-one years later, in 1837, German botanist Hugo von Mohl was the first to describe in detail the tiny structures that contain chlorophyll in leaves. However, it was another German botanist, Arthur Meyer, who studied them more in-depth and found the structures inside the chloroplasts (which he called “autoplasts”) known as grana.

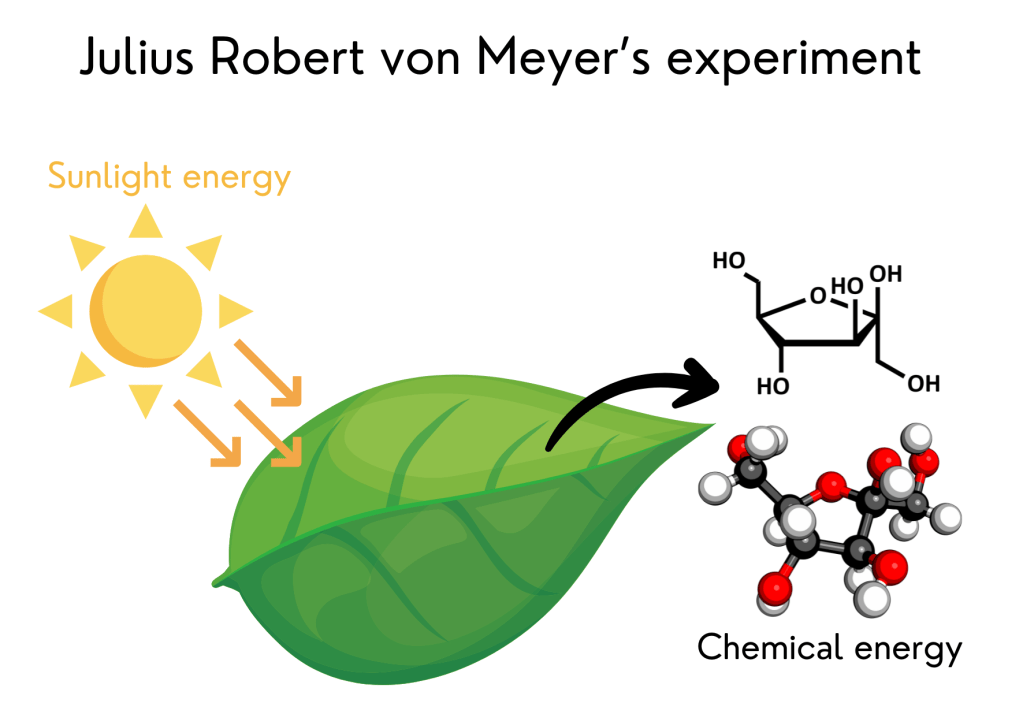

7. Plants transform sunlight energy into chemical energy – Julius Robert von Mayer’s experiment

In 1845, the German physician and physicist Julius Robert von Mayer proposed that plants transform the energy from sunlight into another type of energy: chemical energy (more specifically sugars), which they use to grow.

8. Plants make sugars from carbon dioxide and that is what they use to grow! – Julius von Sachs’ experiment

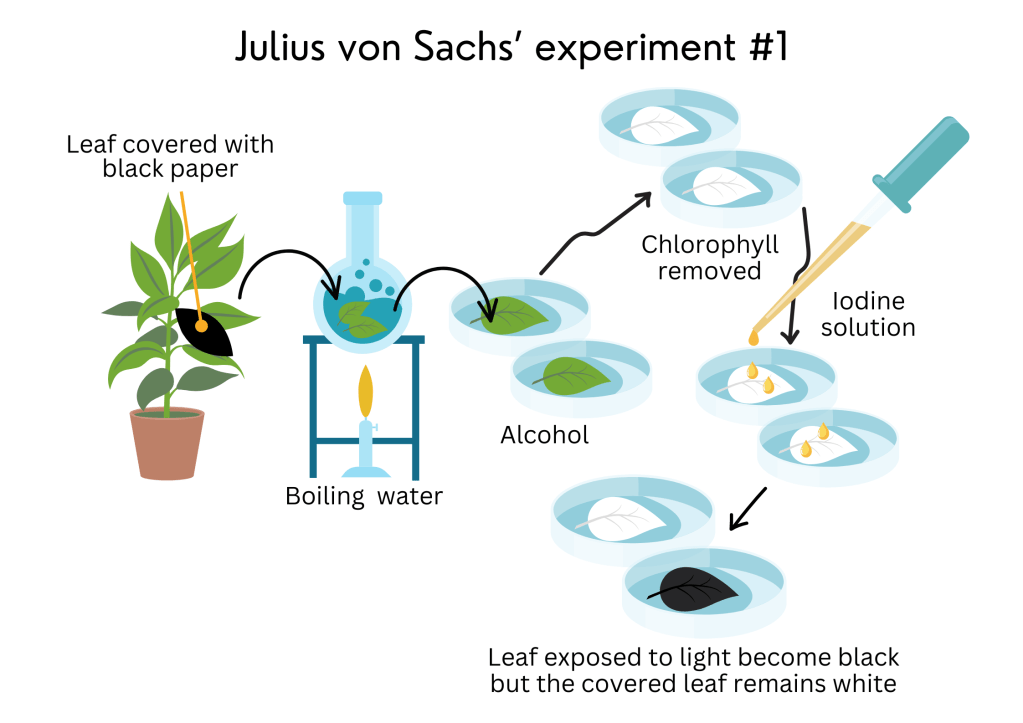

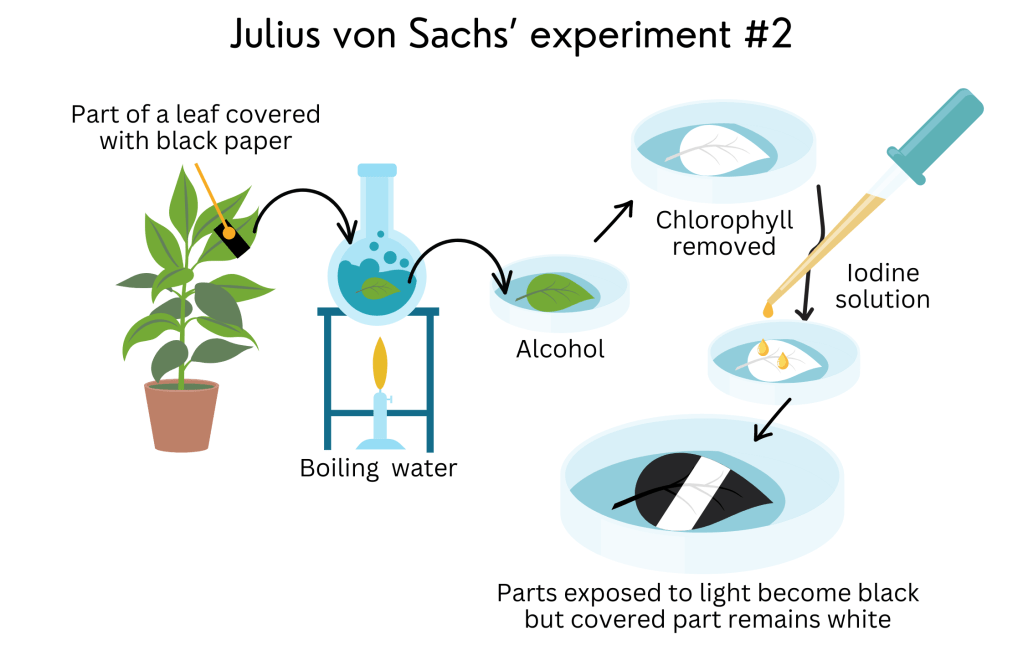

It was Julius von Sachs, a German plant physiologist (a scientist who studies how plants “work”), botanist, and author of many textbooks, who showed how plants make their own food (sugars) and how they store their food as starch.

In 1854, he performed an experiment where he covered one of the leaves of a plant for twelve hours using a dark piece of paper. Then, he took off this leaf and another one that remained uncovered under sunlight. He put the two leaves into boiling water and then into alcohol. The leaves turned white because the alcohol removed all their chlorophyll. He then added a few drops of iodine solution over both leaves. The leaf that received sunlight became stained black, but the covered leaf remained colourless.

He repeated the experiment, now covering just part of a leaf with the dark paper and leaving it under sunlight. After “bleaching” the leaf and adding iodine over it, only the parts that received light became black, and the covered part remained white. That happened because iodine really likes starch and colours it black. Only the parts of the leaf that received light produced sugars and stored them as starch in the chloroplasts. The covered part did not receive light and, therefore, did not make starch through photosynthesis. With this experiment, Sachs showed that sugars are made in the green parts of a leaf through photosynthesis and stored as starch and that this process needs light to happen.

9. Chlorophyll is responsible for the transformation of sunlight into sugars and the production of oxygen – T.W. Engelmann’s experiment

Another very important experiment was performed by the German botanist Theodore Wilhelm Engelmann. In 1881, he conducted an experiment using a prism to split sunlight into all the colours of the rainbow. He focused this rainbow on a tank where he grew some algae called Spirogyra (which have this name due to their spiral chloroplasts) and a lot of “oxygen-eating” bacteria. Since these bacteria could not survive without oxygen, they grouped around where the algae released oxygen.

He noticed that more bacteria were grouped where the blue and red lights were focused. He knew that blue and red lights were the lights that chlorophyll absorbed, so he concluded that photosynthesis happens in chloroplasts and that chlorophyll is what makes photosynthesis happen.

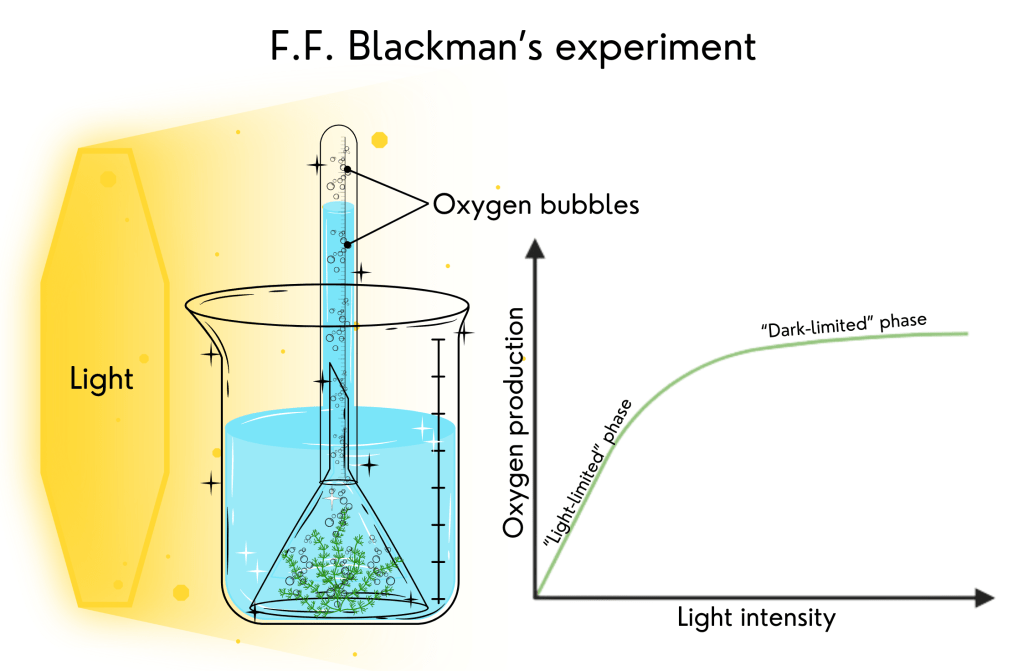

10. Photosynthesis has two different “phases” – Frederick Frost Blackman’s experiment

By the end of the nineteenth century, scientists knew that plants needed water, CO2, and light to make sugars that they store as starch to grow and release oxygen as a waste product. However, there were still a few missing pieces in the photosynthesis puzzle. For example, they did not know if plants would grow forever if they had ‘unlimited’ light or ‘unlimited’ CO2, or if they would grow more if the light intensity or the amount of CO2 increased, or even if any other environmental factor would help or impair their growth.

Frederick Frost Blackman, a British plant physiologist, was the scientist who provided us with some of these answers. In 1905, he performed an experiment using an aquatic plant called Elodea. He placed this plant in a beaker with a water solution of baking soda as a source of CO2, covered the plant with a funnel, and covered the funnel with a test tube. When the plant received light, it immediately started to release oxygen bubbles. He then exposed this plant to different light intensities, counting the number of bubbles released during a fixed interval of time at each of the many light intensities and took notes of the results to make a graph.

He observed that the number of bubbles did not increase indefinitely with more light. He concluded that photosynthesis is composed of at least two different processes: one that requires light and one that does not. He called this later process ‘dark’ reactions, although it can go on in the light.

He repeated the experiment with higher temperatures because he knew that most reactions go faster at higher temperatures (up to a point). He noticed that there was always something interfering with the number of bubbles released. When the amount of CO2 was low and the light was weak, the plant released just a few bubbles, and the temperature did not interfere. When the amount of CO2 was adequate and the temperature was higher (35o C), the number of bubbles increased when the light intensity increased. That means the ‘dark’ reactions were going faster with a higher temperature. But if the light is weak, the number of bubbles was not higher at 35o C than at 20o C. And the number of bubbles did not increase under intense light if the amount of CO2 was low. He then proposed the “law of the limiting factor” (that is: the thing in the lowest quantity – light, CO2, or temperature – limits the number of oxygen bubbles and, therefore, limits photosynthesis).

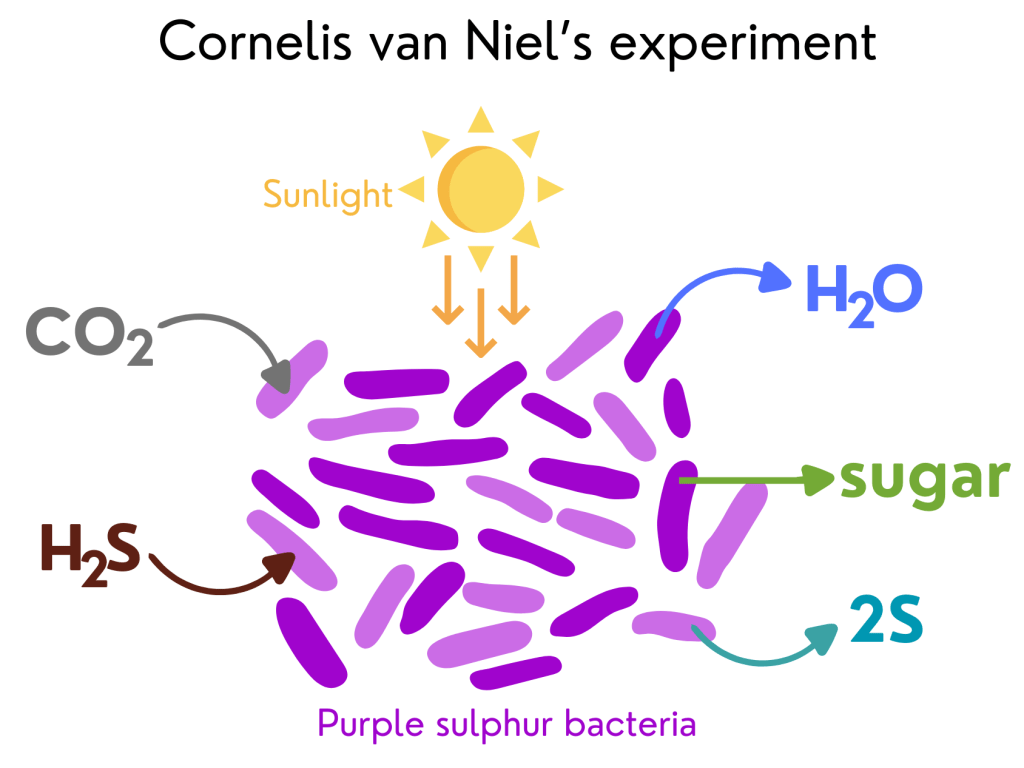

11. Oxygen comes from water, not from carbon dioxide – Cornelis van Niel’s experiment

As the twentieth century began, scientists still didn’t know exactly how plants combined H2O and CO2 to make sugars and release oxygen. Until 1931, scientists believed that photosynthesis worked like this: H2O and CO2 combined to make carbonic acid (H2CO3), and later, light would provide the energy to transform H2CO3 into oxygen and sugars.

Cornelis van Niel, a Dutch-American microbiologist (a scientist who studies microscopic organisms such as bacteria), was the first one to question this idea. In 1931, he was studying purple sulphur bacteria, microscopic organisms that also undergo photosynthesis, but they use hydrogen sulphide (H2S – a colourless, flammable, and extremely dangerous gas with a “rotten egg” smell) instead of water and do not release oxygen. Photosynthesis for these bacteria has the following chemical equation*: CO2 + 2H2S –> (CH2O) + H2O +2S.

In these bacteria’s photosynthesis, light breaks H2S into hydrogen (H) and sulphur (S). Then, in a series of ‘dark’ reactions, H is combined with CO2 to form sugars. Since their photosynthesis had many similarities with plants’ photosynthesis, van Niel came up with the idea that, in plants, light would be used to break water into H and O. Any type of photosynthesis would have the following chemical equation: CO2 + 2HA –> (CH2O) + H2O + 2A. In this general equation, A would be the H donor to transform CO2 into sugars. For purple sulphur bacteria, the H donor would be H2S, and for plants, it would be water.

*Let’s pause a little bit and understand what is a chemical equation.

A chemical equation is like a recipe for a chemical reaction. Imagine you have some ingredients (these are the chemicals) and you mix them together to create something new (this is the reaction). In the chemical equation, the ingredients are represented by symbols and formulas, just like the items in a recipe are listed with their names.

For example, let’s take the equation: 2H2 + O2 –> 2H2O

In this equation:

- 2H2 means you have two molecules of hydrogen (H2).

- O2 means you have one molecule of oxygen (O2).

- The arrow (→) shows that a reaction is happening.

- 2H2O means you end up with two molecules of water (H2O).

So, reading the equation from left to right, you start with hydrogen and oxygen, and they react to form water. It’s like saying, “Mix 2 portions of hydrogen with 1 portion of oxygen, and you’ll get 2 portions of water!”

In simpler terms, a chemical equation tells us what ingredients (chemicals) are involved in a reaction and what new stuff is made as a result.

Now, back to photosynthesis.

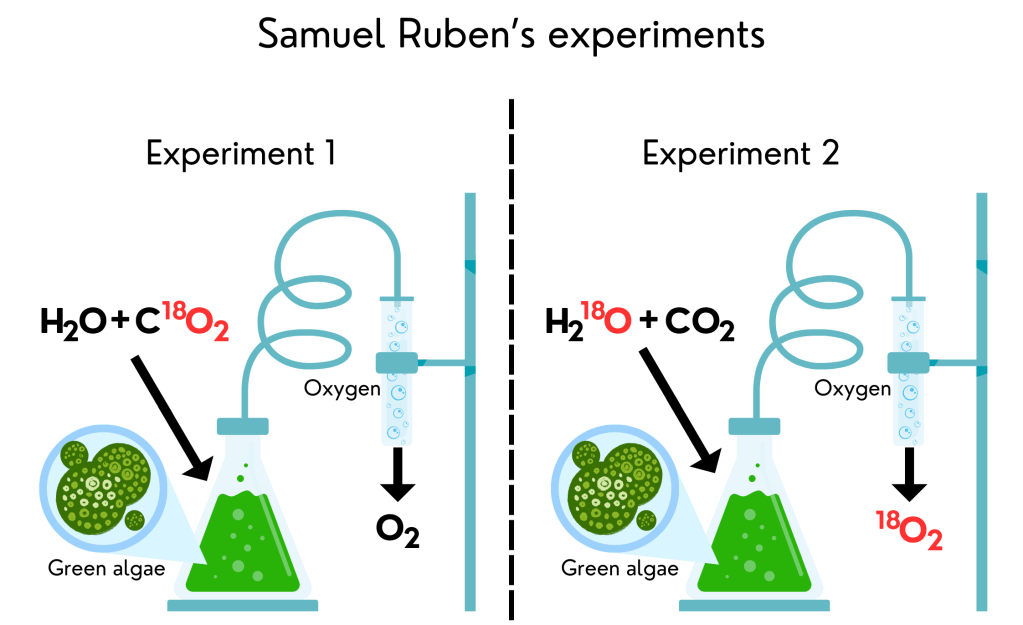

12. Radioactive photosynthesis – Samuel Ruben’s experiments

In science, any idea should be tested. Anyone can have an idea, but what makes it true are the results of very well-designed and easy-to-repeat experiments. Van Niel could be wrong, and oxygen could come from CO2. How would we know? Ten years after van Niel came up with his idea, another scientist, Samuel Ruben, tested it using radioactive water and radioactive CO2.

How would that work, and how does one find radioactive water and CO2? All those molecules we talked about so far (water, CO2, oxygen, sugars, etc.) are made by tiny little “building blocks” called atoms. We represent those atoms with letters. For example, a molecule of water has two atoms of hydrogen (H) and one atom of oxygen (O). That’s why we say water is H2O. Each atom is made by even tinier “building blocks” called protons, neutrons, and electrons (you will also learn more about them in high school). Each atom has a weight and can be found in nature in slightly heavier forms. Those heavier atoms are radioactive. They are very rare, but they exist. Normal oxygen atoms weigh 16 (16O), but radioactive oxygen atoms weigh 18 (18O). We normally don’t write the weight of the atoms in molecule representations because we are talking about the normal atoms, not the radioactive ones. We only write atoms’ weights when we are talking about radioactive atoms. The advantage of radioactive atoms is that, because they’re heavier, one can follow them wherever they go.

Now we can come back to Ruben’s experiment. In 1941, he used radioactive oxygen (18O) to target where photosynthesis oxygen was coming from: water or CO2. He used radioactive water (H218O) and radioactive CO2 (C18O2), both replacing the normal atom of oxygen for radioactive oxygen, and gave them to green algae in two different experiments. Now all he had to do was store the oxygen released by the algae and see if it was radioactive or not. When he gave only radioactive CO2 to the algae, he did not find any radioactive oxygen released. When he gave only radioactive water, however, the oxygen released was radioactive. He then proved that van Niel was right and oxygen comes from water, not from CO2.

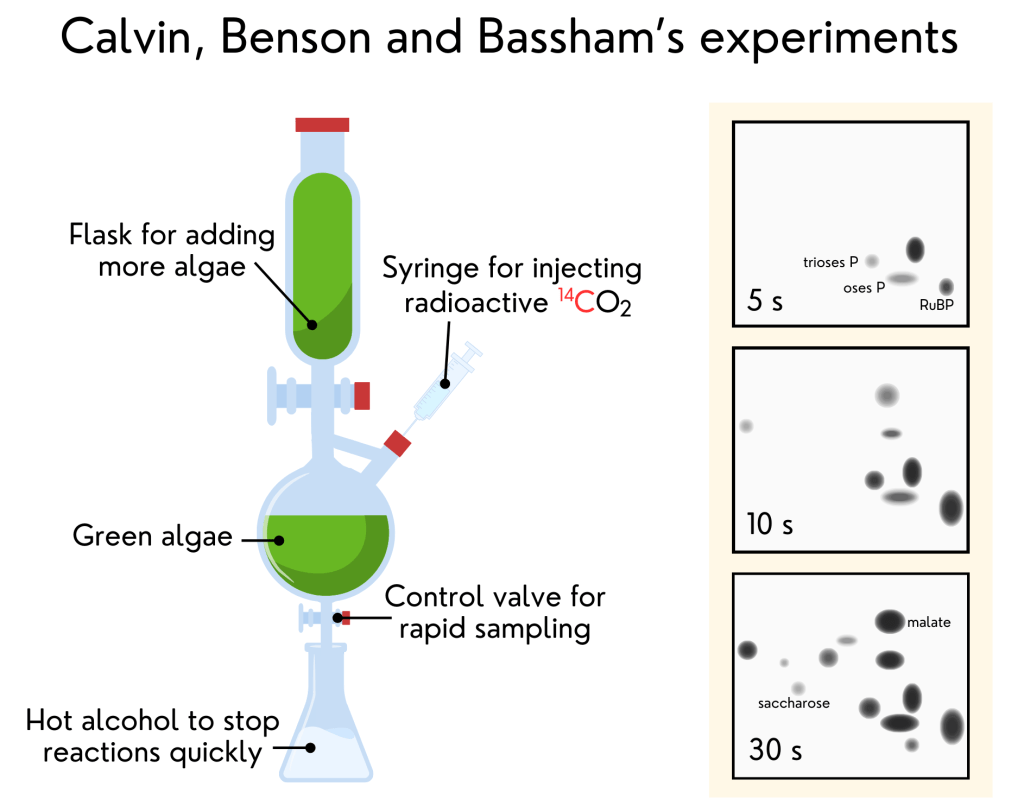

13. The puzzle of how sugars are made – Calvin, Benson and Bassham’s experiment

The twentieth century was crucial for photosynthesis research, finally helping us understand how plants grow. People have pondered this since ancient Greek times, and there has been significant progress since van Helmont’s seventeenth-century experiment. But it took about 400 years to put all the pieces together. By the early 20th century, the only missing part of the photosynthesis mystery was how sugars are made. We knew light split water to release oxygen and donated H to combine with CO2 and make sugars. And we knew that sugars were made in the ‘dark’ phase of photosynthesis. But how exactly? We had extensive knowledge about radioactive atoms then. One could even “make” them in labs, and that was crucial for the last experiment you’ll see here.

In the 1940s, a team of very smart scientists, namely Melvin Calvin, Andrew Benson, and James Bassham, was studying green algae photosynthesis to understand what they do with CO2. These algae were grown in a glass disc resembling a lollipop. Benson had the idea of giving those algae radioactive CO2 and stopping the reactions soon after to “freeze” a moment in time. This allowed them to “see” each step of the reactions transforming CO2 into sugars. This time, the heavy atom was carbon (C), not oxygen. The radioactive molecules formed were separated into sheets of paper. These sheets were pressed against an X-ray-sensitive film to create something called a “chromatogram.” It’s like a photograph showing blobs, with each blob representing a different compound made in different steps from CO2 to sugars. The team could now see each step in the pathway, like a road map. But with many compounds, it took them ten years to understand the correct order in which each step happened. Benson suggested that the first step in this pathway was made by a protein very common in plants. Unfortunately, he left the group and did not finish his work. But he was right. With all the steps organized, Calvin proposed the carbon cycle of photosynthesis, now known as the Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle. Calvin won a Nobel Prize for the discovery in 1961. The other two scientists only received their recognition four decades later.

As I mentioned at the beginning, photosynthesis research is still ongoing, and there are many other interesting experiments and discoveries in the field. Some scientists are even looking at photosynthesis to recreate it in an artificial way to provide us with cleaner and more efficient energy. But this is a topic for another post. Stay tuned.

Want to learn more about the history of photosynthesis? Watch this cool episode of BBC’s documentary series Botany, A Blooming History. And if you liked this one and got interested in plants, watch the other two episodes too, why not?

Leave a comment